For most of the last twenty-five years, if you had asked me to define my training style, I probably would have identified myself as a “joy trainer.” My central defining characteristic as a trainer has been to find and develop joy in playing the game; to determine ways to ensure that doing whatever behavior I wanted was the most fun option imaginable, and that the animal was demonstrably, actively engaged and enthused about the process and the outcome. Over the course of training thousands of dogs, cats, antelope, raccoon, skunk, lemur, crows, chickens, lions, tigers, bears, snakes, and nearly everything else to fairly high levels for hundreds of films, commercials, ads, and TV shows, this technique has served me very well, not only in terms of achieving superb results, but also in terms of having extremely happy animals that LOVE to train and that continue working over long lifespans, and also feeling very good about myself and the lives of my animals.

In that vein, I have often written about the importance, early in training any animal, of determining precisely what that individual finds genuinely rewarding, and understanding the patterns and specifics of reinforcement—when should you use which treats, when play which games, when use which types of praise or petting. What motivations and drives that animal possesses and how best to utilize them.

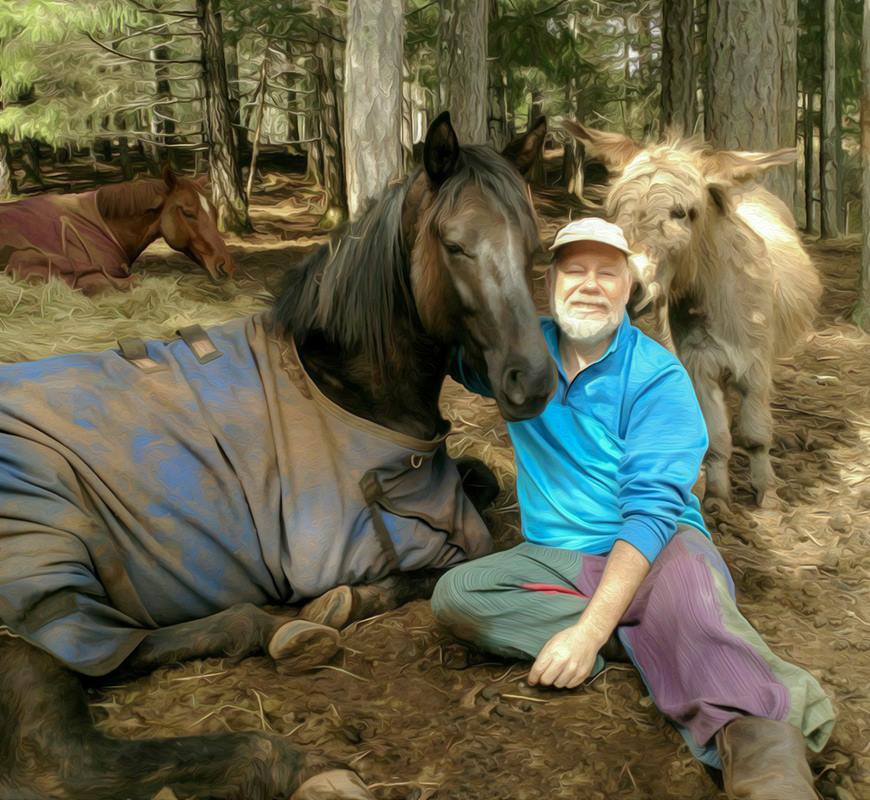

But over the past few years, Veillan, an energetic Lusitano x Arab colt, has helped me to realize that my thinking about joy, drive, and reinforcement was too narrow. When I started training Veillan, I found myself struggling a bit to figure out how to incorporate play and joy into his training. Sure, he had periods of exuberant play, but they tended to be brief and difficult for me to instigate, and trying to play with him while also being safe and not allowing him to rehearse behaviors that would be dangerous and undesirable later in life was challenging.

(It is worth pointing out that my horse experience has been comparatively limited: I rode camp horses as a kid, and briefly participated in an equestrian program in eighth grade, but really had not ridden much. Over the years when we needed to work horses, I always demurred to Lauren who is a lifelong equestrienne. Of course, I started out reading many books, watching, hundreds of DVDs, attending countless clinics, seminars, and lectures, and the vast majority of the principles of training are sufficiently parallel to all other animals that in relatively short order I felt reasonably competent—I knew how and when to release pressure to reinforce a desired behavior, I understood about waiting for relaxation, I was getting pretty good results, my horses were calm and happy and working pretty well, but I had not really figured out how to bring “joy training” to my horses, and none of the horse training experts I consulted seemed particularly focused on joy or exuberance in their horses.)

One day I found myself thinking about something well-known by everyone, and absurdly obvious—that horses are paradigmatically prey animals, and that most of the animals I have trained are predators. In predators, excitation is a powerful positive. Chasing, fighting, killing, eating—good! In prey animals, excitation is generally less positive—being chased, fighting, being killed, being eaten—bad! A central goal for any prey animal is to avoid unnecessarily expending calories or risking injury, so exuberant play is problematic. If you watch young predators, they spend huge amounts of time joyfully playing and rehearsing excitation. If you watch young prey animals, they do play and evince joy, but FAR less. In contemplating this, I realized that I was overlaying onto my animals my assumption that “joy” represented the highest ideal. Perhaps, I suddenly realized, different individuals perceived different emotional states as having more or less value than I assumed…

Most of the horses I have known crave above nearly everything else what I will—imprecisely—call “tranquility.” Tranquility is a complex notion. It includes relaxation, calmness, contentedness, safety, harmony, peace, clarity, certainty, confidence, comfort, balance, and connectedness to friends, self, and environment,. A horse is happiest when all these things come together, although different horses may weight the individual components differently, and to a large degree spends its entire life trying to return to tranquility, to remove whatever factors are interfering with that return. Certainly, play and fun can be used, to great effect, in horse training, but they must be used in service of helping the animal achieve its emotional holy grail.

I started thinking about different dogs who had worked primarily in different drives, and realizing that not only were their drives different, their ideal energy states were different. Loki was happiest in a very relaxed state, Slate finds relaxation almost unpleasant and wants to be vibrating, Flint enjoyed an almost violent tension. Even though they each had play drive and retrieve drive, the emotional tone of their play was very different. As I contemplated each of the animals I have trained, I found myself more and more recognizing that each of them had an ideal energy state, and that training them worked best when I could match my energy, intentions, and actions to that tone, and mindfully help them achieve that state.

One of the central tasks for any animal trainer is to find ways to help each animal recognize that performing the desired behavior is the path to maximizing whatever energetic and emotional state brings that individual the most bliss.